When my doctor tells me that I need to lose weight, I could tell him that I’ve tried 6 meals per day, 1 meal per day, eat early, eat late, low carb, low fat, joined a gym, bought an exercise bike, and everything else. I don’t tell him that. Instead, I say, “No shit. Unless you want to write a script, let’s move on.”

My doctor is about my age, used to wrestle for St. Ignatius and knows what’s up.

I’m not at the point where I need a prescription for a weight–loss drug, but if he wrote me a script, it would probably be for Ozempic. It’s popular, but the ads for Ozempic list so many side effects. Drug companies want people to know what they are selling, but don’t want to get sued by omitting a side effect. They list everything, but without the detail to make the information useful.

I like to read the research, and for Ozempic, which is generically called “semaglutide”, I found this The New England Journal of Medicine Semaglutide Study to be most useful.

In this double-blind trial, we enrolled 1961 adults with a body-mass index (the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters) of 30 or greater (≥27 in persons with ≥1 weight-related coexisting condition), who did not have diabetes, and randomly assigned them, in a 2:1 ratio, to 68 weeks of treatment with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide (at a dose of 2.4 mg) or placebo, plus lifestyle intervention.

“Double–blind” means the participants or the doctors don’t know who is on semaglutide and who is getting the placebo. They have plenty of participants, they picked fat people, and followed them for 16 months. “Lifestyle intervention” means they were supposed to eat clean and exercise. It looks like a good and relevant study.

Table 1 says that the participants are between 33 and 59 years old, and between 183 lbs and 280 lbs. Other demographic and initial medical stats are provided.

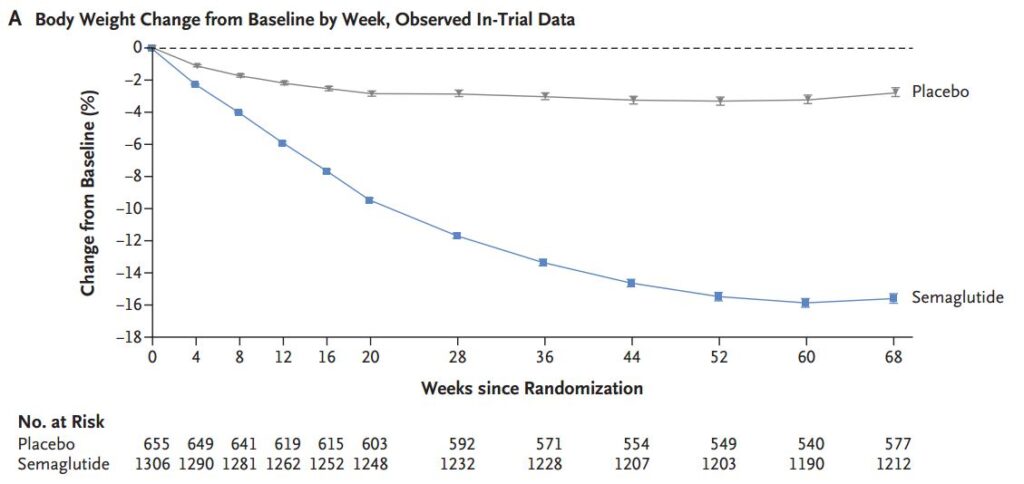

Figure 1 shows the weight change results. For our purposes, we can ignore the distinction between “in-trial” and “on-treatment”. Here’s Figure 1A. The diet and exercise group lost 2%, the semaglutide group lost 16%. The effect is real, but it’s the side effects we want to investigate.

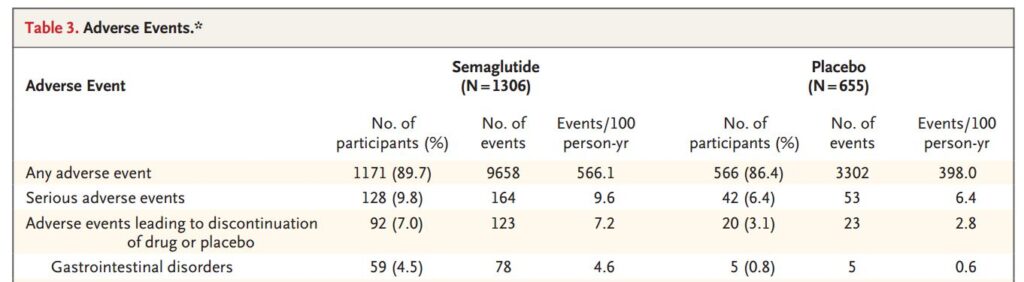

Table 3 lays out the adverse effects. Everybody is exercising and eating less, so even the Placebo Group can experience adverse effects. Here is a truncated portion of that table.

Almost everyone had adverse effects (89.7% vs 86.4%). That’s probably needing to poop after getting jiggled up from exercising. There is a bigger difference in serious adverse effects (9.8% vs 6.4%). ‘Serious’ is a judgment call. All of the participants are fat, and some may not have ever exercised. For both groups with serious adverse effects, it was about 1.3 occurrences in 16 months.

Keep in mind that Table 3 lists any adverse event that happened to almost 2000 fat people who started exercising and dieting in a 16 month period.

Table 3 shows that gastrointestinal disorders (nausea, diarrhea, vomiting or constipation) are the majority of complaints. These adverse effects were experienced by 74.2% of the Semaglutide Group and 47.9% of the Placebo Group. These occurred 4.4 times for the Semaglutide participants and 2.4 times for the Placebo participants.

Honestly, to lose 32 pounds, having a dicky belly every four months doesn’t sound too bad.

On the up side, participants in the Semaglutide Group had fewer cardiovascular disorders (8.2% vs 11.5%) and psychiatric disorders (9.5% vs 12.7%)

I’m not a doctor, just a guy who reads the research and isn’t adverse to medication if the risk/reward ratio is favorable. This study has more medical data, but doesn’t address the positive effects on knees, joints, and overall quality of life resulting from dropping 16% body weight. Most of us should eat better and exercise more, but this study says that loses you 2% body weight. Sure it’s a good idea and I’d feel better, but 4 pounds ain’t shit.