“When my peers are found responsible for multiple instances of inadequate citation, they are often suspended for an academic year,” wrote the student who sits on Harvard’s honor council, which adjudicates peer academic-integrity violations. “When the president of their university is found responsible for the same types of infractions, the fellows of the Corporation ‘unanimously stand in support of’ her,” as the body declared in a Dec. 12 statement.

The Harvard Corporation is supposed to safe-guard the prestige and reputation of Harvard. This was a public and a high profile scenario. They should have seen it coming when they encouraged someone without the record in academia to be the president of Harvard. They probably felt backed into a corner, but they could have played dumb and done their jobs while everyone was watching.

Ms. Gay’s defenders accuse conservatives of using allegations of plagiarism to take her down, which is true. But it’s also true that such lapses, and even more-serious academic-integrity offenses, are too often ignored or excused—much like petty crimes in cities with left-wing governments. The result: declining standards and increasing dishonesty on college campuses.

This is a logical fallacy called an “ad hominem” attack. The defenders attack the people laying out the infraction rather than address the underlying problem. Here are other logical fallacies.

Of course her supporters aren’t going to present the allegations. They are already aware of them, and want to move on. People who are politically aligned, but have doubts about her, are not going to stick their necks out.

Friends who teach at colleges say faculty often don’t report plagiarism or cheating to administrators because the process of doing so is laborious, and students often get off with a slap on the wrist. This is the same reason police in Democrat-run cities don’t make arrests for crimes such as shoplifting. It isn’t worth the hassle since the punishment is trivial.

Short-term incentives rarely reward, and often punish, integrity. Personal and organizational reputation pay off in the long run.

This may explain Ms. Gay’s repeat offenses, which should have been identified by peer-reviewed journals that published her papers. Yet peer reviewers typically are unpaid and often hand the task over to grad students who are reluctant to criticize esteemed academics’ work.

If integrity were easy, everyone would have it.

Stanford’s Faculty Senate last spring passed a motion to amend the honor code to permit exam proctoring because “current mechanisms are insufficient to ensure the academic integrity of our degree programs.” The Undergraduate Senate tried to block the amendment, claiming it violated Stanford’s “shared governance” model.

Did you catch that? At Stanford, exams don’t have a proctor. That means that for a midterm or final, the students are not supervised. The article makes it more clear.

Under the college’s honor code, students are supposed to report on misconduct by peers, but instructors aren’t allowed to supervise exams. Teaching assistants hand out tests and then leave.

This recalls the remote learning that resulted from the Covid shutdown. Administration intentionally avoided any consideration or discussion of exam integrity. In the summer of 2020, it was obvious that we would remain in remote mode for Fall quarter. I talked to the principal about the lack of assessment integrity. It would be impossible to keep students from cheating on quizzes and tests.

My suggestion was to use the gyms and cafeteria as testing sites. Teachers would provide tests or quizzes to the proctor, along with a list of resources that could be used. Students could schedule their quiz or test any time between 7 am and 9 pm, seven days per week. With 1400 students and about one assessment per teacher per week, students could be adequately separated. Keep in mind that by that time, we knew that students were at little risk and associated with friends freely.

The principal had no interest in any attempts to mitigate cheating. In fact, the administration often encouraged “grace”. That was Ed-code for don’t ask much of students and pass everyone.

The result was that low-quality students cheated shamelessly. Eventually, the best and most conscientious students were looking foolish. They still tried their best to learn, but cut corners. One result of the shutdown was degrading the morality of all of our students. They lost respect for the school district, and by extension, the society.

There’s no evidence for any of the students’ complaints. But professors of introductory STEM courses say some students may feel increased pressure to cheat because they lack precalculus skills. Could it be that Stanford is admitting unprepared students to meet its diversity goals, which makes it more difficult for them to succeed in STEM courses?

It is often suggested that diversity goals lower the overall rigor of a school. If admission standards are lowered to meet diversity goals, then a professor is loath to fail the unprepared student. A professor would also want to have an objective grading rubric. If diversity students are graded on a different scale, eventually lawsuits would follow from academically prepared students. The solution is to reduce the rigor for all students.

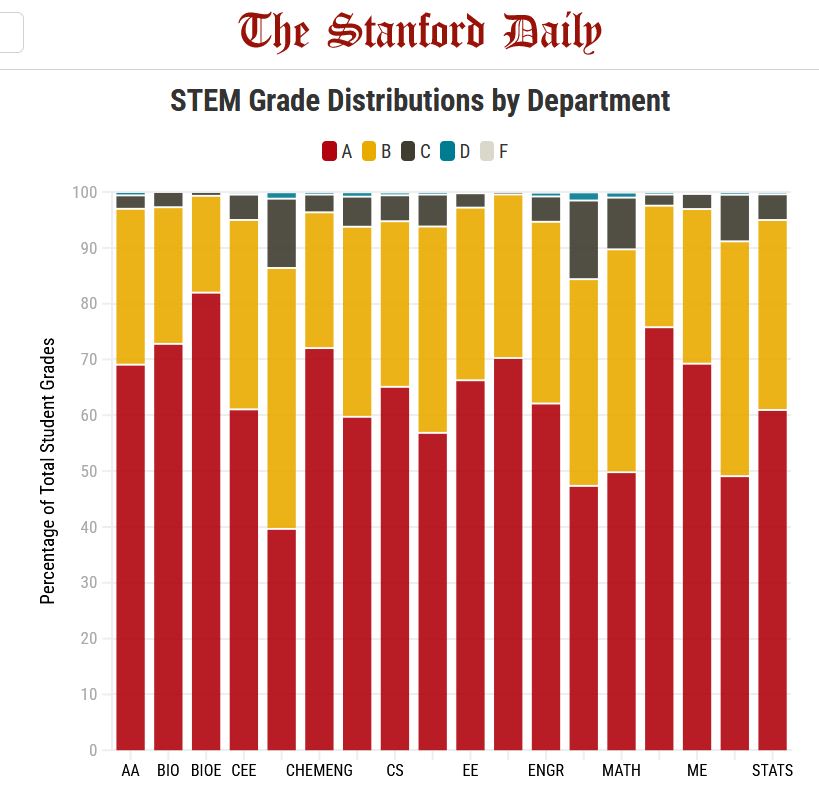

That has happened to Stanford. Here is the grade distributions for STEM departments at Stanford. This is from The Stanford Daily. The red bar indicates A’s, the yellow bar indicates B’s.

Almost everyone gets an A or B in any STEM class. From the article, Human Biology is the most rigorous course with only 85% getting an A or B. Chemistry is also tough, with about 86% getting an A or B.

This is Stanford. Yes, the students are smart, but if upper-level engineering courses are giving an A or B to 98% of the class, this is not a challenging curriculum.

Much as the retreat from “broken windows” policing has produced more crime in progressive cities, colleges’ failure to enforce academic-integrity standards has created an air of impunity among students that is leading to more bad behavior, including harassment of Jewish students. Is it any surprise so many students graduate lacking a moral compass?

Universities have traded away their reputations for a political agenda. Public schools have done the same. There are two solutions that would improve our education system.

First, remove race or ethnicity from all student records. Don’t recognize it for admissions or use it for any data analysis.

Second, with instructors, implement an expectation that the class average should be 85%. That is still very high, but it’s a start. Instructors already have an incentive to use an objective scoring rubric. By implementing a lower class average, instructors will demand more from students.

Public school and universities should be honest and transparent with this implementation. It will take time for the general public to get used to a competitive education. Even now, there are people that think a 3.8 GPA in college actually means something.

When I graduated from OSU in the 1980’s with a Mechanical Engineering degree, I had a 3.05 GPA. A 3.0 GPA was about the line for a good student. I don’t know what employers consider the cut-off to be now. At Clemson, I finished my Master’s with a 3.5 GPA. I put in nearly constant effort. At John Carroll, I was certified to teach Physics and Math and had a 3.95 GPA. That was in the 1990’s, and some grade inflation was already happening.

At JHU, many classes were in the Education Department, but I did take four courses in Math and four courses in Physics. One physics class, Electrodynamics, I had no real understanding anything. The first day, we had a problem that looked like this.

Sure, I know what a triple integral is, and the other thing is a gradient and there is a vector cross product, but all together? Forget it. There were only three students in the class. Father Nichols gave me a B, but shit, I didn’t deserve it.

We should be honest. If STEM knowledge is objective, then race and heritage shouldn’t matter. If they don’t matter, then don’t record them. Excellence comes with competition and not every business will want or be able to hire engineers with 3.8 GPA’s. That is the honest truth, and if we have integrity, the system will adjust and be better for it.

What is the alternative? If universities preferentially admit students based upon race and heritage, then less qualified students will be admitted. Professors will get the message that those preferred students should pass the class with a decent grade. That is where we are now, and employers know it. Soon, everyone will know that doctors, lawyers, dentists and engineers of a preferred demographic may not have had a rigorous education. That isn’t racism or bigotry, just the logical outcome of a system that rewards diversity.