NPR: Getting young girls interested in STEM

I abhor reports like this one on NPR.

When I was in high school, I took every shop class that North Olmsted offered because I was good at making things, graduation requirements were more relaxed, and my parents didn’t get involved in course selection.

In “Advanced Woodworking”, there was one girl in the class. Katy told me that she was put in the class by mistake. Her parents thought it was funny, so they wouldn’t sign the drop slip. For her project, she was attempting to carve a fox mask out of pecan wood. Katy worked on it diligently, but it never got any better. I made a table lamp with laminated tines and a spiraling mahogany column. My sister liked the lamp and still uses it almost fifty years later.

Experts say a lack of exposure and access at an early age keep women — especially women of color — out of STEM careers. A youth organization in St. Louis is working to change that.

Girls and boys are different. Everyone but experts, know this. Emotionally, socially, mentally and physically, there are measurable differences between the average girl and the average boy.

LEWIS-THOMPSON: This is one way Kelli Best-Oliver, the founder and executive director of the LitShop, is working to get more girls excited about science and technology, along with engineering and math. She created LitShop back in 2019 as a space for girls to improve their literacy skills and get hands-on exposure to the world of shop class, especially construction. It’s something she says is missing in a lot of schools.

Shop classes are missing from many schools because computer labs and increased academic requirements have left little room for non-academic elective courses. The shop classes that remain are moving toward 3-D printing and laser cutters, and away from hand tools and craftsmanship. At North Royalton, the shop teachers are very knowledgeable and supportive. There is no barrier to girls taking the shop classes that are offered.

HANAAN PETTUS: Like, building everything is, like, super-duper hard to do. But, like, it’s all worth it when you get to see, like, everything that’s finished. And, like – especially with the golf hole that we’re building, it’s so – the reason I keep coming back, even though it’s so hard to do, is that when you’re done, and you get to go play the golf hole that you made, it’s, like, super rewarding.

It isn’t likely that Hanaan will go into STEM. Compared to boys, girls are much more likely to go to a 4-year college. If Hanaan does, she is much more likely to go into a medical field.

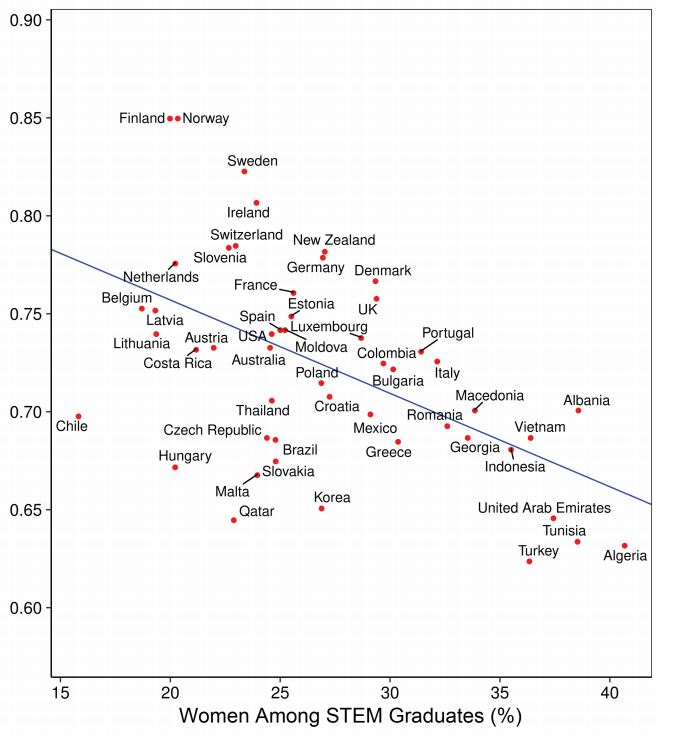

This study, Gender-Equality Paradox in STEM education, explains it clearly. Here’s a graph from the study.

Northern European countries, where women have a high degree of career choice, they don’t tend to go into STEM. Muslim and Arabic countries, where women have much more traditional roles, women have a higher tendency to go into engineering. It’s only a paradox to “experts” who don’t recognize that men and women are different.

LEWIS-THOMPSON: This is one way Kelli Best-Oliver, the founder and executive director of the LitShop, is working to get more girls excited about science and technology, along with engineering and math.

Best-Oliver doesn’t approve of the choices that girls freely make and doesn’t appreciate the contributions that women make to society. Tricking girls into going into STEM won’t help. Women who have a degree in a field in which they have no natural affinity will not make for a gratifying career.

These people with hyphenated last names may have a problem with femininity and masculinity.

As an instructor at Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth, my teaching assistant was usually a woman majoring in a STEM field. My students were between 10 and 12 years old. It made sense to have a mixed gender instructional team in general, but for bathroom purposes specifically.

One year, my TA was a junior in chemical engineering. As we worked together, she didn’t seem interested in engineering or technical topics. Her favorite color was glitter. She told me that. At one point, she told me that she wanted to be an office manager and had no interest in an engineering career.

Chemical engineering is tough, so I asked why she chose that as a major. She told me that in high school, she was on the FIRST robotics team. She had an aptitude in math and science and everyone was telling her that she should be an engineer, so she majored in it.

When she got to college, she didn’t see any robots, but figured it was because she was a freshman and taking a bunch of calculus and physics courses. As a sophomore, she was taking higher level courses, but still didn’t see any robots and was starting to get worried. Junior year, there still weren’t any robots, so she started asking questions. Yeah, engineers don’t drive robots. Nobody drives robots, that’s the whole idea. By that point, finishing with a Chem E degree was her best option.

I get it, but didn’t do it. FIRST robotics is challenging and engaging, but is a kind of engineering marketing. It was never my interest to push people into STEM, just support the students who would thrive in a technical career. My physics partner was concerned about the number of girls taking AP Physics. The classes were about 85% boys. Counselors and progressive teachers wanted more women in engineering. I never did. When asked about it, I came up with a provocative answer.

“I don’t encourage girls to go into engineering.”

Shock and horror detected on the face of the person to whom I’m conversing.

“I don’t encourage boys either. I do everything I can to inform and assist any student with an aptitude and interest in engineering.”

And I did.

I had one student who had an aptitude in physics and enjoyed mechanical problem-solving. He thought he should major in business because he had no other ideas. I told him to be a mechanical engineer, and his career would work out. He did, and so far, he’s doing well.

I’ve had several girls interested in a STEM field, but concerned about any sexism they might encounter. I put them in touch with friends or former students who are women in engineering, so they could explore the issue with someone I trust with direct experience.

LEWIS-THOMPSON: But not everyone who was in LitShop, like 14-year-old Tessa Link, wants to pursue construction as a career. Link aspires to be a surgeon one day. And she says, while she’s been encouraged by the progress made…

The interviewer cuts off this topic, but why? Tessa has a career in mind, why not trust and support her?

We are told that America needs more people in STEM careers. That may be so. To get more people in any career, the constructive approach is to pay more and improve the working conditions. For some reason, people in charge never want to do that. Instead, they make up a bunch of bullshit programs to trick kids into choosing a career that sounds fun.

There is no evidence that we need more women in STEM. What problem does that address? Women are going to college, getting jobs and establishing themselves in careers. Boys are suffering, but for some reason, that doesn’t get any attention.