I’ve been scanning and organizing old photos.

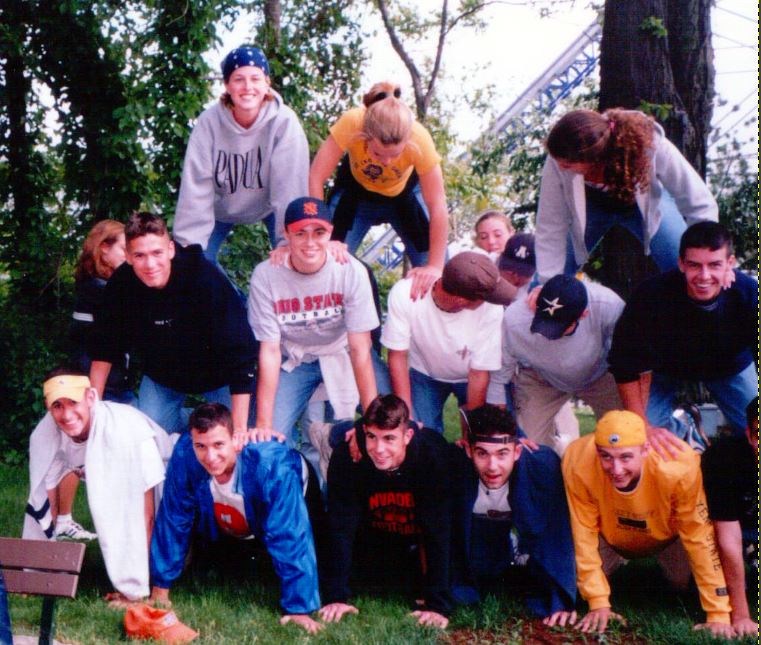

This is from Physics Day at Cedar Point in 2001. Johnny is the student in the center of the bottom row. He was a super kid because he was smart, athletic, had a sense of humor, was polite, mature, good-looking and helpful. Physics came easy to him, but he didn’t brag or show off. I’d call on him when other students were stumped.

You’d think Johnny had it made, but that was the problem. Everyone told him that he could be whatever he wanted to be. A student like that often doesn’t know which direction to go. I don’t know what I suggested when we talked about choosing a career, but he definitely went in a direction I wasn’t expecting.

Johnny’s little brother and sister both took physics, so I knew he was a varsity athlete in college, but that was about it.

Seven years later, I got an email from Johnny. I was at North Royalton by then, so good for him for tracking me down. He was going to be in town for a month before he started his PhD program in Physics at UNC Charlotte. Johnny asked if I’d be available to get a beer. He wanted to tell me about the research he’d done for his Masters thesis. That sounded great, so we set a date. I asked him to send me anything he had on his research so I could read up.

I am very good at physics. Well, really just high school physics, and mostly the aspects of physics that I’d taught. I didn’t know what the hell Johnny was talking about in his published work. Thankfully, the internet provided me with enough background to talk about his work long enough to comfortably redirect the conversation.

Johnny went on to finish his PhD, and got a prestigious post at the Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC) in Menlo Park, California.

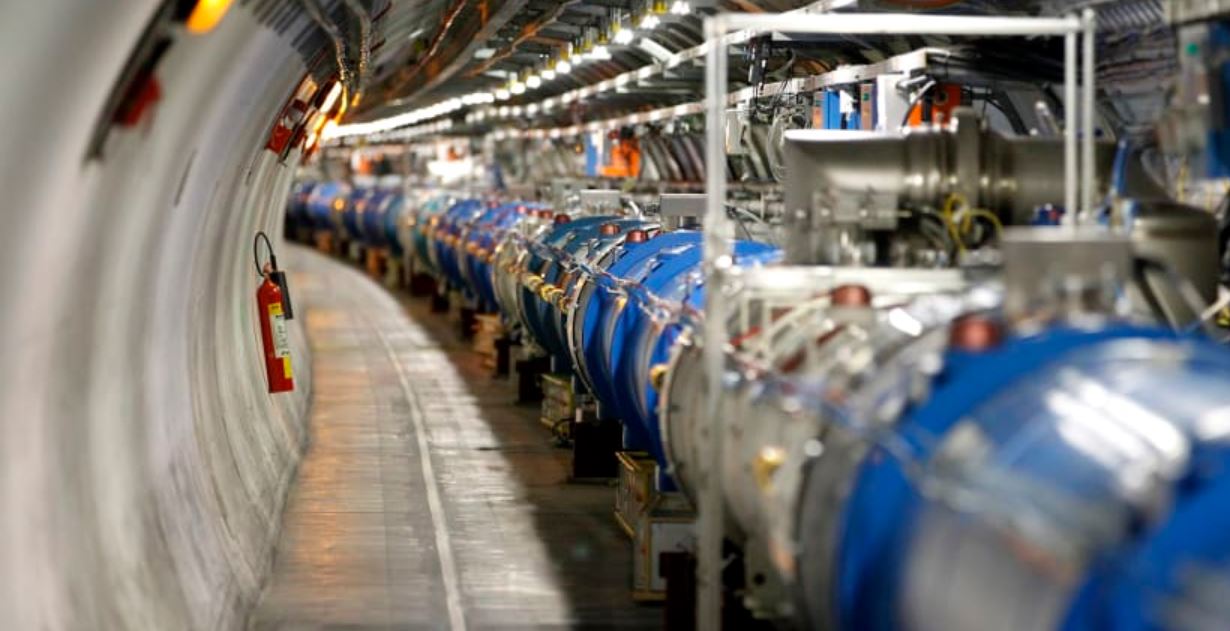

SLAC is a two mile long device to accelerate charged particles, mostly electrons, to nearly the speed of light. Because he was doing particle research, about half his time was spent at CERN, in Geneva, Switzerland. That is the site of the Large Hadron Collider (HLC).

The HLC is a 17 mile long circular track buried 300 feet underground, and is the world’s largest atom smasher. Charged particles are sent in opposite directions along the track, accelerated to relativistic velocities, then crash into each other. The goal is to see what subatomic particles fall out.

Johnny was working there around the time the Higgs Boson was discovered. The Higgs Boson is referred to as the “God Particle”, and is a big deal in physics.

Now, Johnny is making bank managing a lab at Amazon investigating new optical devices.

I do wonder what he made of our conversation over a beer. When Johnny graduated from Normandy, I was the smartest physics guy he’d ever known. When we met up, I wasn’t even the smartest physics guy at the table.

I left engineering to become a physics teacher because I work hard and take pride in my performance. Busting my ass so that Caterpillar could make another billionth of a penny per share of stock, didn’t seem like a good use of my time and energy. Thirty years later, I’m certain that none of my factory automation projects remain in operation. There is nothing left to show that I was ever there.

Thirty years after that Physics Day photo was taken, if you asked Johnny about his physics class at Normandy, he would smile and remember me fondly. I have never regretted my decision to switch careers.

Incidentally, I take no credit for Johnny’s career success. I always felt that I had a duty to my students and brought my ‘A’ game every day. It was a great class. Since Johnny didn’t express a desire to go into Physics, he didn’t get any specific encouragement or advice. I did my job, and Johnny took it from there.