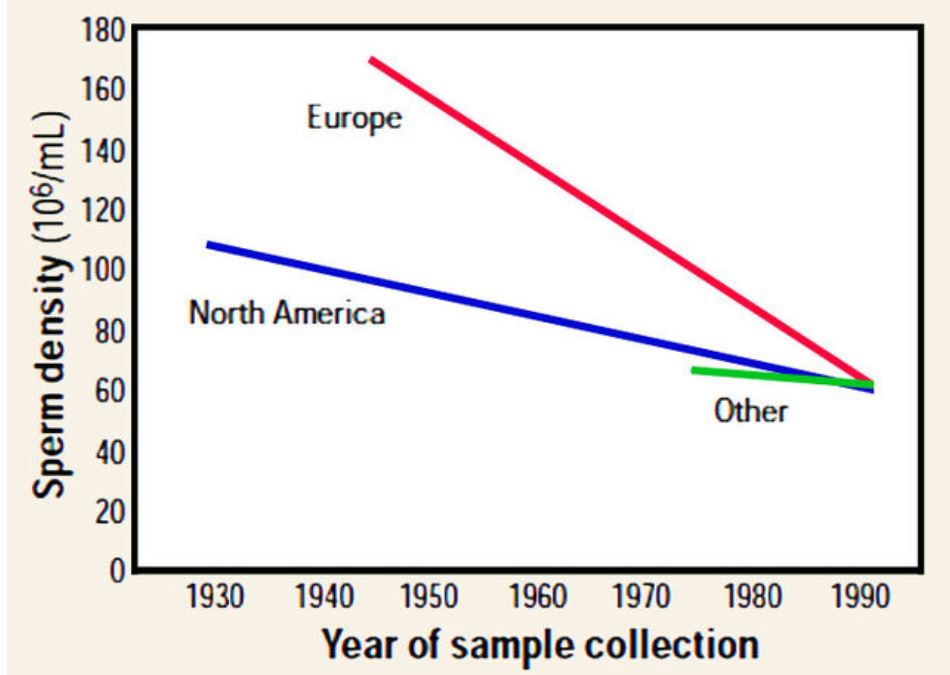

Sperm counts and fertility have been dropping for a hundred years. This could become a problem.

Women having fewer children could be explained by societal changes that mostly converge to women having more life options and control over their fertility. The drop in sperm count is not easy to explain, but everybody wants to attribute the decline to whatever agenda suits them.

In my first quarter at The Ohio State University, I took Bio 100 because, at the time, I was majoring in natural resource management. Everyone majoring in a non-STEM field took it.

The professor was an engaging lecturer, with some wit. He was explaining dominant and recessive genes, and explained how inbreeding increases the chances of passing along harmful, recessive traits. He ended with, “So if you want to have the healthiest kids, breed with someone of a different race.” In 1979, this was a mildly subversive thing to say.

I recently read an article about a related topic that I’d never considered. Outbreeding, that is, mating with someone who is genetically very different, can also be a problem.

The premise is that when two people mate who are genetically very different, some gene combinations won’t be compatible. That incompatibility would show up in complex systems in the body, like fertility and reproduction.

For example, a horse and a donkey can be mated to produce a mule. The mule has useful characteristics of both parents, but can’t produce offspring.

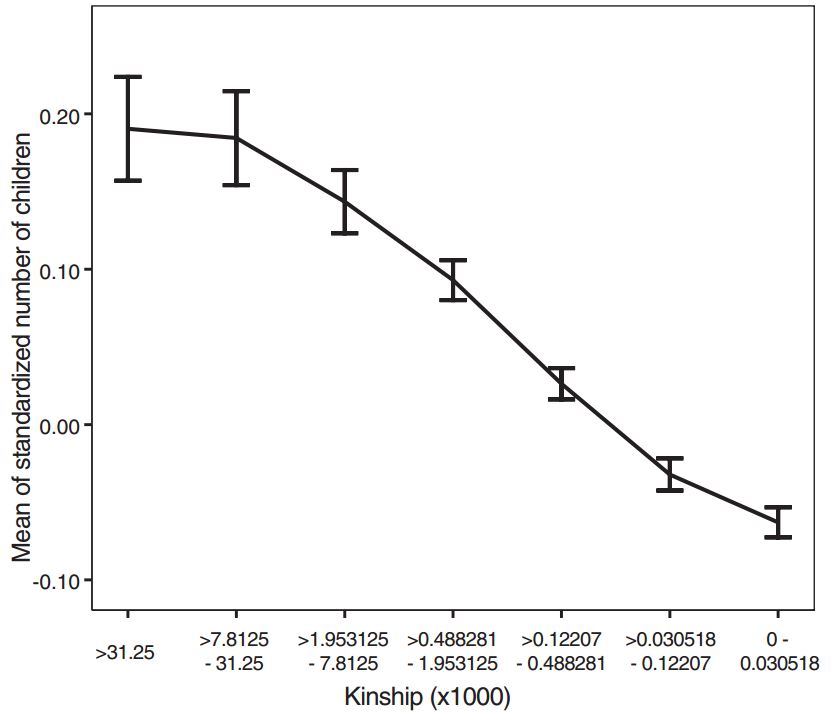

I looked up one of the studies. The Association Between Kinship and Fertility

Our results, drawn from all known couples of the Icelandic population born between 1800 and 1965, show a significant positive association between kinship and fertility, with the greatest reproductive success observed for couples related at the level of third and fourth cousins.

Iceland is a geographically isolated Western country of less than 400,000 people. There is a decent chance that a person may be dating someone who is a relative, so they keep good records. It is also a largely homogeneous with most people sharing the same culture and economic status.

It is written for scientists, so here’s what you need to know. The y-axis is the number of kids per couple. The x-axis is how related they are. On the left, “31.25” are second cousins or closer. Going to the right, is third cousins, then fourth cousins and so on.

The more related they are, the more kids they had. That may be attributed to some weird family dynamic. The most unrelated couples had the fewest children.

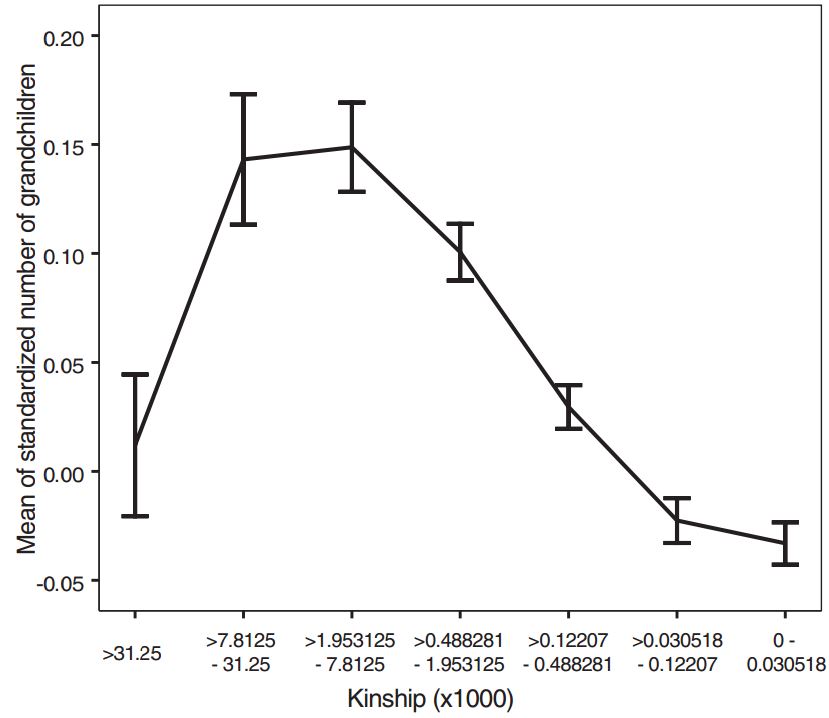

The next graph, shows the number of grandchildren. I’m leaving out a third graph that shows that the average lifespan for children of second-cousin or closer parents isn’t great. There would also be genetic anomalies that may not shorten the life of children, but make them unlikely to find a mate.

There are other studies looking at how genetic differences amongst mating couples effect fertility, but the trends remain the same.

This hypothesis may not hold up, but it warrants further study. We are all human, but there is certainly a lot of genetic diversity in the world. If gene combinations are incompatible, it could alter the ability of the children to procreate.

Companies like 23andMe have vast databases of DNA from their customers. They occasionally ask their customers to take surveys to look for genetic correlations. Perhaps they will participate in a study.

I hope this isn’t one of those science topics we aren’t allowed to discuss or investigate.